Pascaline (Replica)

Zweispezies-Rechenmaschine

1642

Pascaline (Replica)

Two-species calculating machine

1642

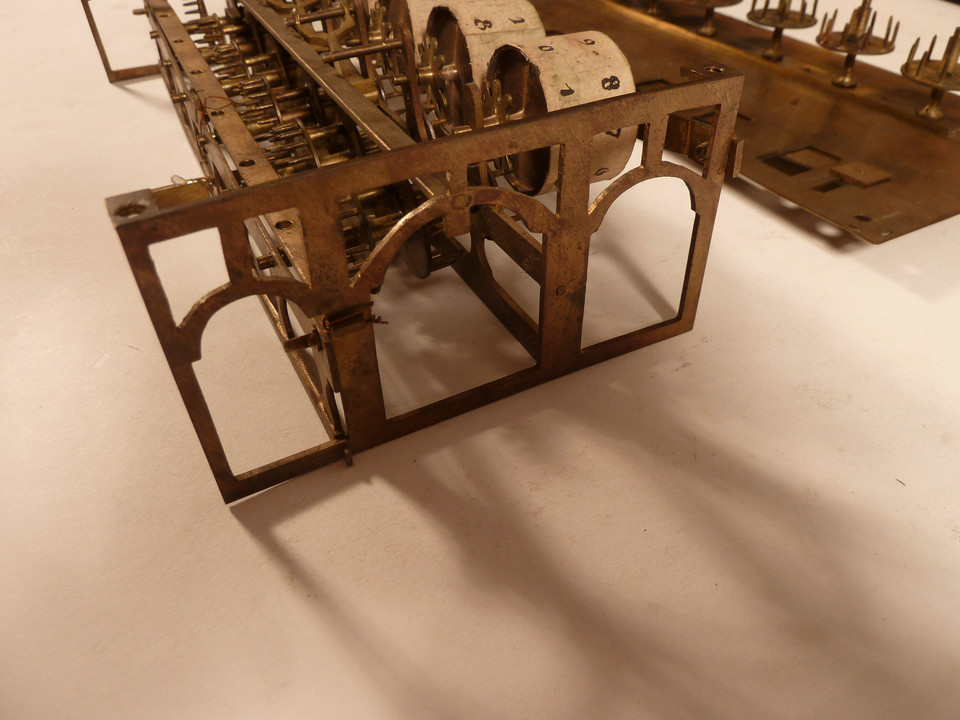

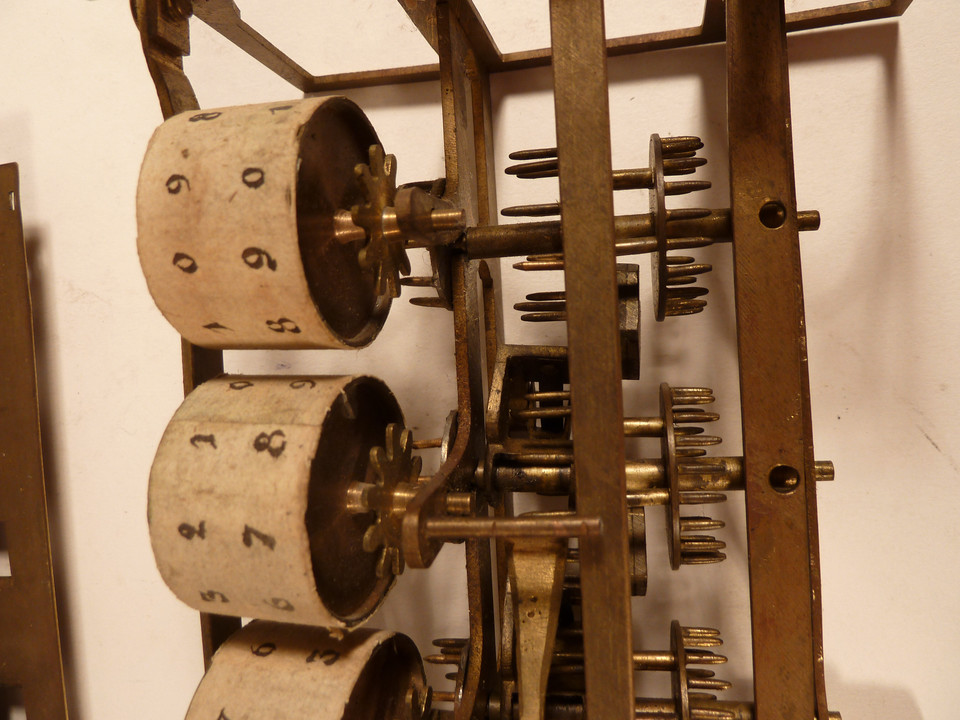

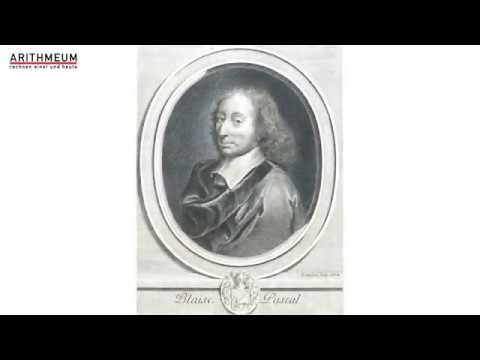

Blaise Pascal built a calculating machine for addition and subtraction in 1642 at the age of 19. For a long time, it was considered the first calculating machine to mechanically transfer tens. It was not until the middle of the 20th century that it was discovered that the Tübingen mathematics professor Wilhelm Schickard had already built a calculating machine in 1623 - the year Pascal was born - which was intended to make calculating easier for him and his friend Johannes Kepler. It functioned over six digits and possessed a functioning tens-carry for both addition and subtraktion. Thus the fame of the first calculating machine is demonstrably due to Schickard, who only had the misfortune that his calculating machines were burnt in the Thirty Year War. Only when Schickard's letters with construction sketches to Kepler were found again in the Pulkowa observatory could his invention be proven. Nevertheless, this did not diminish Pascal's independent inventive achievement. His machines were more elegant and finely constructed and had a tens-carry which functioned perfectly even over ten digits due to the storage of power.

Pascal, who was to help his father, a royal commissioner and supreme tax collector in Normandy, with his work, was not enthusiastic about this. His idea was that a machine should be able to carry out the tedious work of mental arithmetic flawlessly and without effort. In addition, he much preferred to devote himself to his studies of philosophy and theology. That was reason enough to construct a calculating machine. His invention was so groundbreaking that he received a royal privilege, a precursor to the patent, from his father's superior, Chancellor Séguier. Thus, several Pascalines could be built according to his design. Literature often mentions about fifty copies. Today nine Pascal calculators have been preserved. In 2013 another Pascaline appeared on the international market. It was only after a thorough investigation that it turned out to be a replica that was extremely skilfully made. At first it was assumed that it was another of the replicas made by the watchmaker Ernest Rognon, who in 1926 was commissioned to build three replicas as a watchmaker at the CNAM in Paris. One was intended for the Science Museum in London, the second went to the IBM collection in New York and the third was privately owned. These extremely meticulously crafted replicas were also deliberately adapted to the original in terms of their appearance. Thus they appear deceptively real at first glance. However, a detailed comparison with the copy of this provenance shown in the Science Museum in London contradicts this thesis.

The interior of the Pascaline is replicated in much more detail. In fact, the filigree and functionality of the machine correspond very exactly to the original. However, the dedication in the lid proves that it is an exact copy of the calculating machine for Queen Christina of Sweden, the original of which can be found in the CNAM. An enlarged replica of the Pascaline, which was made in 2010 is robust enough to be operated by visitors to the Arithmeum itself and serves as a supplement to this true-to-original replica to enable the direct experience and understanding of this fascinating machine and thus also an important step in the development of mechanical calculation.

- Inventory number:

- FDM9665

- Inventor:

- Pascal, Blaise

- Year of invention:

- 1642

- Main category:

- Ein- bis Dreispeziesmaschine

- Capacity:

- 6 (EW) x 6 (RW)

- Dimensions (H x B x T):

- 9 x 29 x 13 cm